In 2018, The Wellcome Global Monitor reported that only an average of 15.6% of the African population have high trust in scientific institutions and scientists. This report (p. 58) cited two primary factors associated with the level of trust in scientists: 1) learning and understanding science at school or college and 2) confidence in key societal institutions (the government, military, and judiciary). Similarly, in a review of how courtroom linguistic choices impact confidence in the justice system, Liu and Baird discovered that confidence levels are lowest when only a majority language is used in the courtroom, and that use of either a minority language and/or a lingua franca increases confidence levels in the judicial institution (Liu and Baird, 2012). Using more familiar languages as opposed to Western languages has consistently shown increased understanding of scientific concepts and produced better results in examinations

An assessment of the science engagement of African researchers from a prominent university in Zimbabwe cited barriers such as;

- Precarious research funding which can lead to low priority of science engagement,

- Low institutional rewards,

- Government censorship of certain research topics in the public domain,

- Perceived low public science literacy,

- Lack of training programs to equip academics with science communication skills, and

- High teaching loads and lack of time that prohibit extracurricular activities (Ndlovu et al., 2016).

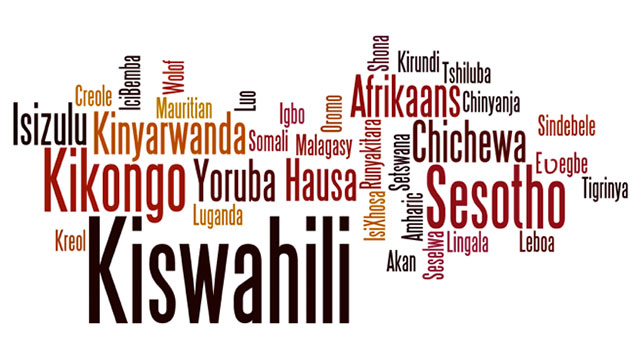

Other barriers include the challenge of making science engagement materials in the many languages spoken across the continent (The African Technology Policy Studies Network, 2010; Karikari et al., 2016). Additionally, many past science engagement programs in Africa have used models that are tailored to Western donor mandates and little to no relevance to the local context (The African Technology Policy Studies Network, 2010, p 23–24), or are largely one-time events with no long-term evaluation, coordination, infrastructure, or sustainability plans (Joubert, 2001).

At this moment in time, scholars are using Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Machine-Learning to solve age-old complex problems like protein folding (Jumper et al., 2021), building models to predict the safety of self-driving vehicles in the human context (Pekannen et al., 2021), and reconstructing paintings from the 1900s (Gaskin, 2021). These same fields are generating tools to translate beautifully diverse and complex African languages to facilitate conversations about technical topics.

At an individual level, what can African scientists do? We can reflect on whether we ourselves can explain aspects of our scientific expertise in African languages. Some examples include the linguist Bienvenu Sene Mongaba, who has created an interpretation of the Periodic Table in the Lingala Language (Sene Mongaba, 2009), a Youtube channel run by one of the authors of this paper (Kago, 2021), where she creates short videos about cell biology topics in the Gikuyu language of Central Kenya, and a book on South African frogs in isiZulu and English (Phaka and Ovid, 2021).

One of the outcomes of the current COVID-19 pandemic is an increased urgency to establish robust biotechnology infrastructures on the African continent. Both the African Union and Africa-CDC have articulated goals to increase the production of vaccines on the continent from 1% to 60% by 2040 (Irwin, 2021). To achieve these goals, African countries need not only logistic and technical capacity, but also societal trust in scientific interventions. We posit that using African Indigenous Languages (AILs) in scientific engagement will go a long way to increase sustainability and longevity of these efforts.

“African governments must look at the languages spoken by their citizens in terms of how they can be utilized to contribute to the welfare of the citizens. It is in preparing our languages for enhanced gainful utilization that we develop them; paradoxically so they may develop us.”—Okoth-Okombo (2001) Read full article here.

Originally published by Frontiers in Communication